AIFF’s VWFW: “Charlie’s Country”

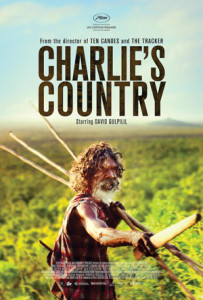

Charlie (David Gulpilil) in Charlie's Country, courtesy of Monument Releasing

Charlie (David Gulpilil) in Charlie's Country, courtesy of Monument Releasing

Varsity World Film Week: “Charlie’s Country” – the Inexorable March of Progress and A Clash of Cultures

– by Lee Greene

As I have already written, this is Ashland Independent Film Festival’s Varsity World Film Week (October 2-8). Twelve films from around the world are being screened daily at the Varsity Theatre in Ashland. And they are all wonderful films. Unlike the ordinary fare being shown at your local cinema, which has little choice but to show whatever their distributor delivers, be it good , bad or indifferent, films get specially selected to be in a festival like Varsity World Film Week. Only the cream of the crop get in. I was invited to screen and review a couple of the films being shown now in Varsity World Film Week and the second one I saw was a 2013 Australian film, Charlie’s Country.

Charlie’s Country is a lushly filmed and appealing story of an elderly Aborigine’s struggle to carve out a place for himself in a world upended by the inexorable march of progress amid a sharp clash of cultures between the old ways of his native Aboriginal roots and the modern ways of the encroaching non-Aboriginal “white man’s” society. The film is primarily being promoted as an interesting and sympathetic tale of an older Aborigine’s clash with the very different “white man’s” culture that has injected itself into and taken over the Aborigines’ native area. But I saw it as something deeper and more profound, a parable of the struggle we all encounter as we age, with progress and change in the world.

Those of us getting on in years all know this passage, to a greater or lesser degree. I have a friend, intelligent, erudite, prosperous, a lover of the arts, who refuses to embrace the latest technology of the modern world – so he has resisted and shunned the technology in vogue in our contemporary culture: no mobile phone, no computer, no internet, no continuous assault on the senses from a technology connection. He holds fast to “the old ways”, which isn’t an easy position to embrace, and leaves him something of an odd duck (a Luddite?) among his peers, let alone the generations behind him, who have mastered the “new ways.” There’s at least a little of that challenge in all of our lives, as we grow older, and the world around us changes. (Why did Facebook have to change how it organizes and displays our timelines? Why did Charter TV have to go digital and change all the channels so I can’t find what I’m looking for anymore? Why aren’t there any pay phones around anymore – where is Clark Kent supposed to re-costume as Superman now, and where are those of us who don’t have a cell phone supposed to make an emergency phone call from? etc.) So most of us can relate first hand to the struggles of the title character, Charlie, in Charlie’s Country, though his challenge is an extreme case.

Charlie’s struggle is exacerbated by the sharp cultural differences between the Aboriginal culture he grew up in, and the world of modern Australia, with a paternalistic government that attempts to exercise control over its citizens’ lives for the benefit and protection of the greater good. The Aborigines once roamed at liberty in “the bush” country, freely hunted and fished there, and passed on customs and traditions like tribal dances from generation to generation. As a boy, Charlie was one of the participants to perform the tribal dance for Queen Elizabeth at the ceremonies to celebrate the opening of the Sidney Opera House.

Now the government has taken over control of everything. Guns and other “dangerous weapons” are licensed and largely banned, rendering hunting nearly impossible. Adults instead are on the dole and shop at the neighborhood supermarket, purchasing and consuming whatever the capitalist promoters of “white society” are peddling. Kids are put in schools, the better to socialize them into the new ways, and so no longer interested in receiving the traditions and customs their elders wish to pass down. The new generation is unfamiliar with and isn’t learning the tribal dance that was such a defining element of Charlie’s young life.

Charlie’s lifelong pal, Black Pete (Peter Djigirr) and Charlie (David Gulpilil) go hunting for buffalo in Charlie’s Country, courtesy of Monument Releasing

Charlie’s struggle leads him on a long, difficult journey to establish a place for himself in his dramatically altered world. Resisting the push to adopt the ways and allures of the new “Australian” world, he attempts to provide for himself by trying to hunt for food instead of settling for the unsatisfying offerings at the local market. When his rifle, spear, and car are confiscated by the police, for being in violation of a variety of licensing and regulatory laws, he tries to retreat deep into the bush country and make a life for himself there adhering to the “old ways.” Exasperated Charlie in conversation with another mature Aborigine: “I have no money left. No food. I’m hungry.” The reply: “There’s plenty of food in the bush. It’s like a supermarket.” Initially this seems to be working out well. Charlie spears a fish in the river and cooks it in (not on) a fire: “cooked just right.” Charlie to himself: “I’m eating well. . . . I have my own supermarket.” But it turns out, it isn’t so easy for an elder to live on his own in the bush, as he has to confront untamed nature and all of its elements. He is repeatedly drenched by heavy rains and chilled by the cold, leaving him coughing, sick, prone and dreaming, and eventually passed out under a rock outcropping in the pouring rain. When the rain stops, he is found unconscious by his friend, hunting buddy, and lifelong childhood pal, “Black Pete”, who succeeds in extracting him from the bush back to civilization.

However, things only get worse, as Charlie is seriously ill as a result of his exposure to raw life. He is flown away from his homeland to the big city (Darwin) where he is hospitalized and finds himself isolated and alone, and connected to all manner of unpleasant, cold, modern medical technology. As soon as he is well enough, he rejects modern medical treatment, and escapes the hospital, leaving him to wander in the city. But the city does have cash machines and he’s still on the dole, so in short order, he’s got the wherewithal to negotiate the city.

“Banned” woman, Faith (Jennifer Budukpuduk Gaykamangu) and Charlie (David Gulpilil) walk around the city (Darwin) in Charlie’s Country, courtesy of Monument Releasing

Then he is approached by Faith, a “banned” black woman (“banned” by paternal government regulation from buying or consuming alcohol), to purchase some “grog” for her and her “family”. Charlie is only too pleased to defy authority and purchase beer and whiskey for these aborigine outcasts. When Faith brings Charlie to her “home” (a field on the perimeter of a city park), a large group of them gather and celebrate their good fortune by drinking themselves into a stupor. This is repeated until, in the middle of one drinking spree, the police arrive to break up the party.

Charlie, incensed at the authorities’ unwanted injection of their values, power and control into the world of his people, attacks the police cruiser, smashing it’s windshield with a shovel. For this and providing alcohol to the “banned”, he is sent to prison, where his identity is further shattered as his appearance is dramatically altered by shaving off not only his distinct and distinguished grey beard and mustache but all of his flowing white mane of hair, leaving him completely bald. We then get to see an extended slice of Charlie’s life in prison, including various scenes working in the prison laundry, repeated prison meals featuring brightly colored slop (the colors change) poured over some form of starch to hold it together, a prison visit from his pal “Black Pete”, various pre-parole meetings with a parole officer, etc. Charlie is a well behaved prisoner, causing no problems, never complaining.

Eventually he is released from prison. “I want to go home now, back to my country where my place is.” We see Charlie back at a campside fire, looking like himself again, with a full grey beard and mane of white hair. After a dissatisfying visit to a local market (“same old junk; same old prices”), we see Charlie back in the bush country. He is eventually approached in the bush by another mature Aborigine, led there by a ranger who has tracked Charlie down, to ask him to come back and teach the kids the traditional dance. Charlie initially declines, suggesting they get “Bobby” to do it instead. But when he’s told Bobby has “smoked too much” and as a result been taken to the hospital in Darwin, Charlie relents. The final scenes show Charlie with the kids. First he is telling them about dancing for Queen Elizabeth at the opening of the Sydney Opera House. Then he is teaching them the dance, and finally leading the kids in traditional face paint performing the dance at a roaring fire.

While that synopsis recapitulates the story in a nutshell, it really doesn’t do justice to the film, which is crammed with beautiful visual touches, subtlety, and fine details. Charlie is well played by Indigenous Australian actor David Gulpilil, who has long been the public face of Aborigines on film. As an extraordinarily skilled sixteen-year-old actor and dancer in 1969, Gulpilil was given a principal role in Nicolas Roeg’s acclaimed 1971 film, Walkabout, making him an instant national and international celebrity. [Wikipedia, David Gulpilil, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Gulpilil] Gulpilil has acted, usually playing an Indigenous Australian character, in 13 more films (most notably, 1976’s Storm Boy, 1986’s Crocodile Dundee, and 2002’s The Tracker) before Charlie’s Country, and has been nominated for and received multiple acting awards. [Id.] In Charlie’s Country, he is surrounded by a large cast of colorful and interesting characters he encounters as his story is chronicled: various members of the Indigenous population he lives among, numerous police constables, an assortment of government representatives, all manner of merchants and shopkeepers, medical providers, a magistrate, characters within the prison, and more. Each of these characters and their interactions with Charlie add to the tapestry of the film, and the sum of all of them makes this an extraordinary film deserving of the hour and 48 minutes of your time it will take to see it. At its simplest, Charlie’s Country is a very compelling and interesting story of an elder caught up in a clash between cultures. But as I noted earlier, at a deeper level, it works as a parable of the struggles all of us encounter with change and progress as we age.

Here’s an opportunity to see the trailer for the film:

The film has showings at the Varsity Theatre, 166 E. Main Street, Ashland, on Oct. 2 & 8 at 9:30 pm, Oct. 3 & 6 at 1:30 pm, Oct. 4 & 7 at 6:50 pm, and Oct. 5 at 4:10 pm. Get tickets at the Varsity Theatre box office or online at http://bit.ly/1VbIdF1. For information and schedules for all 12 films being shown during Varsity World Film Week, see online at http://bit.ly/1YDYO3A.